History buffs and music lovers, gather ‘round—today we’re blending two passions in perfect harmony: the rich, fascinating history of the vinyl record.

Let’s be clear—record players aren’t just stylish relics sitting in the homes of audiophiles and hipsters. Long before the iPod or the Walkman ever existed, record players were the original personal music device. They were revolutionary. For the first time, people could sit at home and choose exactly what they wanted to hear—something we take for granted today.

Before that? It was all about the radio. Imagine a world where your only option was to tune in and hope your favorite song came on. No skipping, no playlists, no replay button. Just passive listening.

To appreciate how far we’ve come—and the cultural shift that vinyl sparked—we’re diving deep into the story of vinyl records: how they began, how they evolved, and why they still matter.

What is Vinyl?

Referring to records simply as “vinyl” is a bit like calling a surfboard “fiberglass” or a bookshelf “wood.” Vinyl is the material a record is made from—not the format itself. But to understand how we got here, let’s rewind a bit.

Before vinyl, records were made from shellac, and before shellac, there were massive, experimental cylinders made of zinc, glass, and other odd materials—all the way back in 1887.

So, what is vinyl? It’s a synthetic plastic known as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), created by combining ethylene (derived from crude oil) and chlorine. Born out of the early 20th-century plastics revolution, vinyl emerged alongside a wave of synthetic materials that promised to outperform natural ones like wood, stone, leather, and metal in both durability and versatility.

Depending on how it’s processed, PVC can become sturdy plumbing pipes—or delicate, high-fidelity phonograph records. (Though we wouldn’t recommend plumbing your house with your old jazz collection.)

While vinyl as a material had existed for decades, it wasn’t until 1948 that it found its defining role in music, thanks to Peter Goldmark’s development of the 33⅓ RPM long-playing (LP) record. From that moment on, vinyl records would become the gold standard for recorded sound—and a cultural icon in their own right.

The Origins of Recorded Sound

In 1877, while working on his groundbreaking inventions—the telephone and telegraph—Thomas Edison inadvertently created another revolutionary device: the phonograph. This early sound recorder and playback machine marked the first time in history that audio could be captured and reproduced. In a June 1878 issue of North American Review, Edison outlined his vision for the phonograph’s future uses, which included music playback, voice dictation, education, and even functioning as a “verbal clock.”

During the 1880s, Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Laboratory took Edison’s original concept and improved upon it, ultimately developing a new version of the device: the gramophone. Unlike Edison’s phonograph, which used wax cylinders to record and play sound, the gramophone read sound from flat, hard rubber discs spun by a hand-crank mechanism. This design paved the way for a more practical and durable format.

In 1887, German-American inventor Emile Berliner advanced the gramophone even further by introducing lateral-cut flat discs—closely resembling the vinyl records we know today. These discs proved far more efficient and easier to store than fragile wax cylinders.

By 1892, both phonographs and gramophones were being marketed to the general public. Edison’s phonograph, in particular, was advertised as an entertainment device offering recordings on brown wax cylinders. However, these early cylinders had limitations: they could only hold about two minutes of sound and were expensive to produce.

A major leap came in 1901 with the introduction of mass-produced duplicate wax cylinders. Rather than engraving each cylinder individually with a stylus, manufacturers began using molds and a more durable wax formula. Known as “gold-molded” cylinders—named for the gold electrodes used during production, which released a golden vapor—this new method allowed up to 150 copies to be made from a single mold, dramatically increasing accessibility and affordability.

The Birth of Vinyl Records

In 1948, with the support of Columbia Records, the vinyl record as we know it made its grand debut—spinning at a then-revolutionary 33 1/3 revolutions per minute. Thanks to microgroove technology and the use of polyvinyl chloride, a standard 12-inch record could now hold up to 21 minutes per side. That’s 42 minutes of continuous music without interruption. For the time, this was nothing short of a miracle.

Not impressed yet? That’s probably because you haven’t been dropped into the year 1947...

Back then, just two years after the end of World War II, home listeners were still spinning 78 rpm shellac records—each one holding about five minutes of sound per side. That meant listening to a full symphony or jazz set required an entire stack of records and constant flipping or changing. So when Columbia unveiled a format that could hold a full album on a single disc, it was a seismic shift. Vinyl didn’t just improve music listening—it redefined it.

Before vinyl, there was shellac—a natural resin secreted by the female lac bug. These tree-dwelling insects left hardened deposits on branches, which were harvested, processed, and melted down to form disc records. Shellac was praised for its moisture resistance and was often called “natural plastic.” But it came with one major flaw: it was incredibly brittle. A single drop could shatter a shellac record into pieces—like dropping a teacup on concrete.

Vinyl, by contrast, was durable, flexible, and could store more sound with greater fidelity. It wasn’t just a new format—it was a revolution.

The Golden Age of Vinyl (1950s–1980s)

Spanning from the 1950s through the 1980s, the Golden Age of Vinyl was a transformative period when records weren’t just a format—they were the heartbeat of global music culture. This era saw vinyl rise from a technical innovation to the dominant medium for music consumption, shaping the way fans experienced sound and how artists expressed their craft.

In the 1950s, vinyl LPs allowed artists to go beyond the limitations of the 78 rpm single, enabling them to create full-length albums that explored deeper themes and showcased broader musical range. This period laid the groundwork for the birth of rock 'n' roll, jazz innovation, and the popularization of rhythm & blues. Artists like Elvis Presley, Miles Davis, and Frank Sinatra helped define this new era, and their albums became cultural milestones pressed into wax.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the LP evolve from a product into an art form. With the rise of concept albums, gatefold covers, and album artwork that became just as iconic as the music itself, records were now visual and emotional experiences. Bands like The Beatles, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and Fleetwood Mac used the LP format to craft cohesive, narrative-driven projects that couldn't be fully appreciated in single-song snippets.

By the 1980s, vinyl had reached its cultural peak. Despite the rise of cassettes and the early signs of digital audio, vinyl remained the gold standard for audiophiles, DJs, and everyday music lovers. Record stores flourished, turntables were a common household fixture, and album releases were major cultural events.

From jazz to rock, soul to punk, the Golden Age of Vinyl wasn’t just about music—it was about identity, connection, and the ritual of dropping the needle on a fresh groove. It was a time when albums were held, admired, and played from start to finish—a tactile experience that no digital format has fully replicated.

The Decline and Rise Again (1990s–Present)

In 1982, Sony Corporation introduced the world to the compact disc, and with it came a seismic shift in how people consumed music. CDs were sleek, durable, and portable—and unlike vinyl, they didn’t require careful handling or bulky turntables. With CD and cassette players becoming standard in cars and home entertainment systems, the public quickly embraced the new format. For vinyl, the future suddenly looked grim.

As the 20th century neared its end, vinyl sales plummeted. The 1990s marked a low point for records, with CDs and cassettes dominating store shelves and consumer preferences. Music buyers prioritized convenience, portability, and digital clarity over the tactile, immersive experience of playing a vinyl album.

For a moment, it seemed as if vinyl was destined for extinction. Industry analysts and music fans alike predicted that turntables would gather dust and that records would become relics of a bygone era. But vinyl wasn’t finished yet.

How The Vinyl Record Works

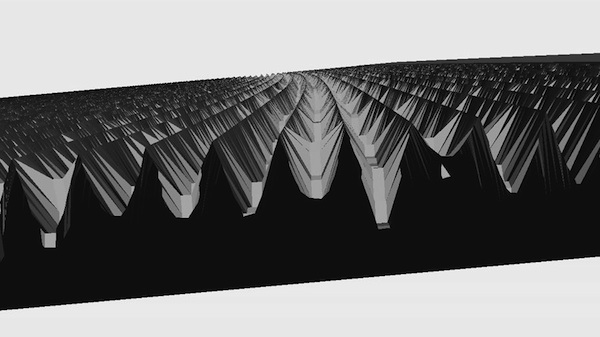

The way vinyl records produce sound is a fascinating blend of mechanical engineering and acoustic science. Often affectionately called “lacquer discs,” vinyl records are pressed with microscopic spiral grooves—tiny indentations that act like a physical fingerprint of the original sound recording. (And yes, that might just be where the phrase “groovy” comes from.)

To play a vinyl record, you place it on a turntable, which spins the disc on a rotating platter—typically at a speed of 33⅓ revolutions per minute (rpm) for full-length albums. A long, precise tonearm hovers over the record, ending in a cartridge that houses a stylus—usually made from diamond or sapphire for durability and precision.

As the turntable spins, the stylus drops into the record’s grooves and vibrates in response to the bumps and dips—essentially tracing the physical waveform etched into the vinyl. These vibrations travel through the cartridge, which contains a piezoelectric or magnetic element. This component converts the mechanical vibrations into an electrical signal.

That signal is then sent to the turntable’s amplifier, which boosts it and sends it to your speakers—transforming those microscopic grooves into the music you hear.

As the record plays, the stylus gradually moves inward, from the outer edge toward the center of the disc. Each side typically holds 20–30 minutes of music. Artists often sequence their albums carefully—ending Side A with an energetic or emotional track to encourage listeners to flip the record and continue the journey.

Vinyl Records in Modern Times

In today’s digital age, vinyl records have made a remarkable comeback, becoming more than just a nostalgic relic—they’re now a powerful symbol of musical authenticity. While streaming dominates daily listening, many fans, especially younger generations, are turning to vinyl for its physical presence and emotional value. The large-scale artwork, the act of placing the needle, and the ritual of listening from start to finish create a deeper, more intentional connection to music. Vinyl isn’t just about sound—it's about experience.

Economically, vinyl is also reshaping the music industry. In recent years, vinyl sales have outpaced CDs, with artists releasing exclusive pressings and limited editions to boost engagement and revenue. From pop stars like Taylor Swift to indie bands, musicians now see vinyl as both a creative and commercial asset. It offers higher profit margins for independent artists and helps create collectible moments in a streaming-first world. Vinyl’s role today is clear: it bridges past and present, offering a timeless, physical counterpoint to our fast-moving digital culture.

Conclusion

Reflecting on the rich history of vinyl, it’s natural to question what lies ahead. While the future of the music industry remains unpredictable, one thing is certain: vinyl will continue to hold a special place in the hearts of devoted listeners. Its distinctive sound and the immersive, hands-on experience it offers ensure that vinyl won’t fade—it will endure as a cherished format for generations to come.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.